October 28, 2009

A True Halloween Mystery Case: Tammy

It usually starts to be visible in the morning. In fact, when I ask 7-year-old Tammy, she's very clear on this, and disagrees with her mother. She says that sometimes she knows it's coming on when she's in her bath the night before. She starts getting itchy. Mom remembered this, but said that she examined her and could find nothing. Then the following morning Tammy is really itchy, and starts to get red around her lips. By the end of the afternoon, her lips and face are red and swollen. Her face is very itchy, and the painful to touch. It looks like a swollen water balloon. Mom says that she gave her an antihistamine and that helped a little with the itch but did nothing for the swelling. Within a day or so, the swelling gradually diminishes, the skin on her face cracks and peels, and everything goes back to normal.

That's not the worst of it, her mother adds. It's her privates, too. The whole sequence is just the same: itch, then swelling and redness and more itch and tenderness, and then it gradually goes back to normal. It's never as bad as her face, she added.

The first time, Tammy was taken to the Emergency Room. They gave her some steroid medicine and an antihistamine. This seemed to help the itch, and the problem went away in a day or so. The ER doctor told mom that it was poison oak [our West Coast relative of poison ivy]. She told me she knew that wasn't possible, but didn't say anything at the time. A week later, it happened again, just the same way. This time, her mother didn't take her to the ER, she just gave her some antihistamine and took her to her regular doctor. The doctor focused on the first symptom, the redness around the lips and told the mother based on this that the child has a serious food allergy and should be tested right away.

At the allergist, Tammy was tested for sensitivity to: milk (2 kinds), cheese (3 kinds), fish (4 kinds), shellfish (6 kinds), wheat, corn, oats, rice, rye, barley, walnuts, almonds, pistachio nuts, Brazil nuts, pecans, sunflower seeds, sesame seeds, hazelnuts, cottonseed, olives, chocolate, beef, pork, chicken, soybeans, tomatoes, cucumbers, squash, pumpkin, egg white, egg yolk, peanuts, strawberry, raspberry, blueberry, blackberry, carrots, lettuce, broccoli, melons, pears, apples, peaches, 4 different molds, 4 different dust mites and their droppings, 16 different inhaled pollens from grasses/trees/weeds/flowers, and dogs and cats. The tests were negative.

Tammy's mom found her way to me. Our first visit took 2 hours.

I gave Tammy a quick exam, but since she wasn't having any symptoms, I didn't expect to find anything. I didn't.

What took the time was my insistence on hearing about the most recent episode—just a few days ago—from beginning to end. The first thing I caught was the lips. Mom said red around the lips when she told me the first time. Was it around them, or were the lips red? Around, she said. So did the lips get swollen? Yes, but only after the whole face was swollen. I asked Tammy if her lips got itchy or tingly. They didn't, and neither did her tongue or throat.

And what was she eating the day before this would happen? All the usual stuff: sometimes macaroni and cheese, sometimes a hot dog, sometimes a chicken nugget or salad or peanut butter sandwich. The same stuff she ate on every day that it didn't happen. Did she go anyplace different before it happened? No, the same old places as always. Home, play park, grandma's. Does grandma have pets? A dog, who plays with Tammy when they're in the vegetable garden helping grandma.

In fact, that's how mom knew that it couldn't be poison oak. Grandma was a meticulous gardener, and started growing vegetables with Tammy so that they'd have a project together. They grew the vegetables that Tammy picked out: pumpkins, of course, both orange and green speckled ones and white ones, along with squash and cucumbers. They have just harvested the last crop, and in the upcoming weeks, Tammy explained, she would help her grandmother chop up the vines and leaves for compost to help the soil and prepare for the winter. Her grandma had bought her pink gardening gloves that matched her own.

I asked both Tammy and her mother about every possible body part. Did her eyes itch? How about her palms or feet or scalp? And other symptoms: coughing, wheezing, sneezing, runny nose, itchy nose, rash of any kind?

The ER doc was on the right track but didn't have the time to listen to the whole story from beginning to end.

The reaction that most people get to poison oak or poison ivy is intense itching, sometime with blisters. It's from a plant resin that sinks into the skin and causes a big reaction from the immune system. It often does take at least several hours, sometimes more than a day, for a reaction to be noticed. But the resin binds to the skin and the immune reaction takes weeks to resolve. Besides, the mother knew that the grandmother's garden had no weeds. Tammy didn't venture into unknown bushes.

There are many different kinds of allergies. Some cause a sudden flood of signals into the bloodstream, setting off an unfortunate sequence of events which can include swelling of the airway, which can be lethal. Others are slower or more superficial, with itchiness or redness the only symptoms. Food allergies can be particularly worrisome because once you've eaten something, you're stuck with it until it breaks down into pieces of proteins too small to be recognized. With the slower variety of food allergies, you might first feel a tingling or itchiness in you mouth, lips, or tongue. It is a general principle that the parts most affected are usually the parts that got the most exposure to whatever it is that you're allergic to. The pink moist skin of our lips, mouth, tongue, and a few other spots is particularly sensitive. These tissues are often the first to sense and react to a problem.

But not in Tammy. Her lips were not affected, it was the regular skin around them. Then gradually, the rest of her face. The fact that her body as a whole was unaffected is further reassurance that this signal, whatever it was, was not coming from the inside. A reaction to a food would send its messages everywhere. And what about the privates?

Some patterns ring familiar after years and years of experience. If the ankles and hands and other areas of exposed skin are affected, it's likely something that brushed up against the person. If it's the face and...then it's the places the person touches, and the offending agent was carried on the person's hands. We all touch our faces unconsciously; we all must answer nature's occasional call.

So I agreed with the ER doctor that this was a contact dermatitis. But it wasn't poison oak. I made the mother tediously recount the most recent episode from beginning to end. When was the previous episode, and when the one before that? Mom, as she tried to recollect, realized before I did that these episodes occurred the day after Tammy was with grandma. We knew, however, that Tammy wasn't allergic to the dog or to any of the vegetables in grandma's garden. We were almost there: it was contact dermatitis, bad enough to make Tammy's skin swell but not getting into her system; she was contacting it at grandma's house but not at her own house or school or park. What was different about grandma's house?

The garden.

Mom pointed out that she had been tested for allergy to all of the garden plants.

But this reaction wasn't from eating any of the vegetables. There are many allergists and laboratories that can test for food allergies. But how about the stems? I checked the 3 different big commercial testing labs, but none of them offered such a test.

The family of plants that includes cucumbers, melons, gourds, and pumpkins are fun to grow because they grow so fast. To support this rapid growth, they have thick stems with lots of sap. This milky sap can cause severe skin irritation. Most of these plants have bristly hairs which themselves—even without the sap—can cause a skin reaction. A key clue in Tammy's story was the gardening gloves that prevented any symptoms on her hands.

When you take your kids to the pumpkin patch, feel free to pick a pumpkin from the ones that are waiting on the rack or in the bin. But beware of the pumpkin patch itself.

October 25, 2009

Transition Issues -- A Definition

Pretty much every week, I’m in an airplane. At this point, I have flown so often that nearly everything is routine about it. Those of us who board earlier in the process are already sitting as the rest of the passengers walk on. Nearly everybody is using this time to talk on their cellphone, text messages, or do something technological until the plane takes off, when all electronics must be shut off. So it was not unusual that the guy across the aisle from me was chatting breezily on his blackberry phone in a foreign language as the plane filled up. I heard the big door shut and sealed by the flight attendant, who announced that all electronics must be turned off. They walked up and down the aisle. Politely, they reminded a few of the passengers that they had to finish using their laptops or phones. The big jet was being backed out of the gate. One of them tapped him on the shoulder and gestured, with a smile, to his phone. He nodded his head in cooperation as he continued to talk on the phone. The plane started to taxi to the runway. Both flight attendants approached the man and told him verbally that he must shut off the phone. He kept talking but nodded his understanding. They walked away, as the plane got closer to the end of the runway. The plane stopped. Both pilot and co-pilot, in uniform, emerged from the cockpit and came to the man. He saw them, smiled and held up his index finger, as if to say ‘I’ll be with you in a minute.’ One of the officers said, “In 15 seconds we will have you removed from this aircraft by Federal marshalls. You will be taken to Federal detention. You are committing a crime and will have a criminal record.” The man, showing an unexpected facility with languages, seemed suddenly to understand English. He abruptly said into the phone, “I gotta go,” and turned off the device.

Ask any parent about getting their child to turn off the video mid-story and wash their hands for dinner. Sometimes they wish they had a couple of Federal marshalls to call.

This is the first essay of several on transition issues, techniques, and objects. I hope some readers find these ideas helpful.

Transitions are the times of overlap between what we are doing and what we are doing next.

This is my own definition, so it doesn’t appear just this way in parenting books. But I think it applies throughout our lives. In babies, it could be transition between being awake and being asleep, or maybe between being held and being put down into the crib. For preschoolers, it might be the transition between one activity and another, say coloring vs. playing with blocks. In school, there are transitions between classroom work and lunch, lunch and active play, then back to class. By high school, it may be all about just getting off the phone.

Being able to navigate successful transitions is a life skill. Our frequent flyer, for example, nearly spent a night in jail. There’s an important balance to be struck between being bad at this and being too good at it.

Many children are brought to me for evaluation of what is thought to be an attention problem. (Because I do this very carefully, I often find other issues. ) Other children are brought in for behavioral advice because every transition results in a tantrum.

Being able to pay attention is also a key life skill. It enables us to listen to a story, to follow crucial directions, and to fall in love. Even if it didn’t help us get through school, it would be important in establishing human relationships and stalking prey on the savannah.

But it’s also important, and little studied I think, to be able to break off our attention when appropriate. Otherwise, we might end up on the No-Fly List.

There’s something about certain activities, I believe, that interferes with the normal balance of transition controls in the brain for certain children. For some, video games tap into something very primal. There aren’t many activities that a child can do for so many hours that they ignore bodily functions. There’s a clue about autistic spectrum disorders here, by the way. Some children with ASDs will continue to do a repetitive activity until they fall asleep exhausted, or are distracted or stopped by somebody. Maybe it’s making a sound, maybe it’s not so benign. Decades ago, some of these were assigned the unfortunate categorization of self-stimulatory behaviors.

Max was brought to me because his mother didn’t know what to do. In kindergarten, he did fine with the class activities and didn’t get in trouble. In school, he could transition between circle games and coloring and learning to write his name just as well as everybody else in the class. He was not a behavior problem. At home, however, it was a different story. No matter what he was doing--playing with blocks, playing with his robot people, or looking through picture books of trucks--his mother couldn’t pull him away. She’d plead with him to come to dinner, bargain with him to get into the bath, but he always said words that were the equivalent of holding up an index finger as if to say, ‘I’ll be with you in a minute.’ When she was more assertive, a long and unpleasant tantrum exploded.

Max was not, in my professional opinion, developmentally abnormal, attention-challenged, or emotionally unstable.

It was hard for him to give up a fun activity. Because of his normal developmental stage, it was almost impossible for him to envision himself in a future situation, even if that future was only 15 or 30 minutes away. So even when his next activity would be even more fun, he could never appreciate it. So there was never an incentive to stop what he was doing and move on.

For the record, he was brought to me with his mother complaining that he was constipated. It was only after I asked lots of questions that the whole story emerged. He focused so intensely on whatever he was doing that he never wanted to stop, even for brief bathroom breaks. After a while of ignoring the feeling that he had to go, he no longer felt that he had to go. This led to a spiral of holding it in until it turned to concrete.

The first step would be helping him get to a less intensely-focused state, in which he'd be less and less invested in his current activity and more ready for the next. I suggested a gentle reminder at 20-minutes. Mom could tap him on the shoulder and let him know that a change was coming. As expected, he would nod his head or indicate he understood but otherwise show no indication that he would comply. Then again at 10-minutes, but this time with a little more discussion. At 4 or 5 minutes, he should be told to shut off the video. He won't, but he also won't be surprised when it happens. Maybe he won't like the transition, but at least he'll be prepared for it.

October 22, 2009

A Glimpse of New Autism Research

I was lucky to have once taken a course given by Fred Volkmar, and have attended many scientific talks by him. He and colleague Ami Klin are, in my professional opinion, the people who know more about autism and autistic spectrum disorders than anyone else on the planet. (Over in my Amazon store, I have put some of the key books that they have written about Autistic-Spectrum Disorders in the section called ‘The Autistic Spectrum.’) Several years ago, I attended a talk by Volkmar at which he showed video of groundbreaking experiments with autistic people.

They would be shown a clip from a movie. If I remember correctly, it was a scene from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The movie is heavy on dialog and interpersonal drama, but not too much action. Subjects in the study were rigged with a camera that tracked the movements of their eyes and mapped that to the screen. In this way, the experimenter could see and keep track of exactly what the person was looking at on the screen. Even if the people on the screen were screaming at each other, if you were looking at the sofa, this apparatus would pick it up.

Why did they even try this elaborate experiment?

Though they never discussed it with me, it probably has its roots in the problems people on the autistic spectrum have with social interactions. Even when their language and intellect is fine, eye contact can be awkward or avoidant.

What they found was that typically-developing subjects would follow the drama by watching the actor’s eyes, and change the eyes they looked at when the speaker changed. Those on the spectrum kept looking at the actors’ mouths. As the scene unfolded, this pattern became more and more clear.

Jump forward maybe 5 years or so to today, when I found a recent research study by Klin and others in Archives of General Psychiatry. Now they used the same kind of apparatus, but had 2-year-old subjects. They spared the kids all the friction between Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton by producing their own carefully-orchestrated movie of a friendly grown-up talking and singing and playing games with them onscreen (like pat-a-cake).

The eyes of the children followed remarkably different paths. The ASD children looked at mouths. The typical children looked at eyes. Even a group of developmentally-delayed children looked at eyes. The more severely autistic the child, the more they seemed to prefer mouth over eyes.

Wait—is it the mouth that’s so interesting or is it just because it’s moving? So in another experiment, they showed just an animated outline of the actor, both upright—which you might be able to figure out—and upside-down, which looks nearly uninterpretable. The experiment was run again with an animation that showed movement coupled with sound, which they called ‘audiovisual synchrony.’ This proved to be the most attractive of all.

Why is this so important?

There are two big reasons that come to mind right away. First, there is no test for autism. There’s no lab test, nothing. With some basic technological standardization, this apparatus and its interpretative software could be an essential tool not just to identify affected children but also to measure how affected they are. That’s been a dream of those working in the field for a long time. Often, kids were given the diagnosis because they weren’t speaking, even though their social interactions were generally OK. Sometimes those with real trouble with their social interactions would not get that extra coaching they need because their language was normal (Dr. Volkmar, by the way, literally wrote the book on Asperger’s Syndrome). An autism diagnosis was usually dependent on the examiner. An objective test of any sort would help to figure out if there really is a growing incidence of autism. And it would enable all of us to figure out if an intervention were actually helping.

But there’s another big reason, though the authors of the study barely hint at it (rightly so, since they didn’t study this). Research on babies over the past 100 years or so has shown that babies—even newborns—prefer the sight of a human face. The faces we make when we hold and play with a baby are thought to be essential for both normal brain development and normal development of attachment and social interaction. What if they show that this aberrant gaze issue is present in infants that eventually have an ASD? It’s a great thing because kids won’t get diagnosed at 2 or 3 or 4. Early intervention has a chance, at least, of having a substantial beneficial impact.

And there’s my hidden agenda…. If we hook a 1-month-old up to this camera and show this animation, and the baby is diagnosed with autism, what does that imply—once and for all—about MMR vaccine, which kids don’t get until they’re 12-months old?

Addendum: I found another interesting research study, though it’s a little heavier in the molecular biology. This study found that some common genetic variants, all on Chromosome 5, correlated with autistic-spectrum-disorders. I’m hoping that this results in prenatal testing. And then maybe a few more children will get the shots they need.

October 18, 2009

The Human Pacifier, Part 3

In this case, it would be a luxury to examine every tree, but I had to see the whole forest, and it was on fire. Sure, the care that most families would get probably wouldn't include trying to fix these problems, and probably wouldn't include even looking for these problems. It just takes too much time. But that's not who I am and not how I practice. And it's not the best thing for the patient.

So I decided not to try the many possible interventions in series, one after another, in a way that would eventually yield a diagnosis and medical approach to the problem. This family needed my help right away, and they couldn't wait around, trying one thing or another just so I could claim a diagnosis. I explained this to them, and they seemed relieved. I suggested doing everything at once. Hopefully, something will work. Once the problem is fixed, we could, if desired, peel back the interventions layer by layer as if an onion. Perhaps in this way, we could arise at some diagnostic insight but not wake up the sleeping baby.

First, let's establish a transition object. The transition is a fairly nonspecific one—perhaps between wake and sleep, or from being held by mommy to not being held by mommy, or maybe between a sense of security and insecurity. Sometimes it's called a security blanket. The most well known, perhaps, is that of Linus, created by Charles Schultz. I suggested that the parents get a baby blanket like those used in the hospital nursery: soft flannel, but nothing fancy, hand-knit, family-heirloom, or large. A hand-towel or even a washcloth will do. Every time the mother nurses the baby, she needs to hold this between the baby's body and her own. It will pick up her scent, breast milk, sweat, and the baby's drool, spit-up, and scent. This too, has been studied. Even babies just a few weeks old can recognize the scent of their own mothers. Whenever the baby is being put to sleep, even if in a parent's arms, the cloth has to be there. Maybe, at those shallow levels of sleep, the sensory feedback gently provided by this transition object will be just the reassurance necessary to send him back to a deeper level of sleep.

I told them to bite the bullet and put the baby in the other room. Yes, get rid of the co-sleeper. Every time the baby is getting to a shallow sleep level, he smells fresh muffins and needs his mother to provide them. I want her to be available to comfort him if needed (this is NOT about crying-it-out), but I want him to work a little harder for it. If you are just barely awake and smell the fresh muffins baking, vs. just barely awake but have to get dressed and drive to the muffin shop. Either way, you get your muffins. But I bet you sleep a little longer if you have to go to the store. I expect that changing his pattern of sleep/wake will not be easy at first. I didn't suggest letting him go cold turkey on this. That's what the transition object is for. How much worse can it get?

The removal of the infant into the other room, I hope, will enable mother to miss some of those subtle vocal cues that she has been conditioned to hear and cause her awakening. Maybe if she's not hearing the baby talk in his sleep, she won't have to wake up unless he really wakes up. And both she and the baby know that he's not really eating all through the night. The nursing for 1-2 minutes is not long enough for a nutritive meal. It's for brief comfort.

The baby's eczema must be treated. I prescribed some lotion with a very weak steroid in it to use on the dry patches and on the dry patch on his scalp. Hopefully, this will relieve the baby's itch and let him sleep better and longer.

If the baby has heartburn, which seems consistent with some observations of the parents, he's not going to like being put down flat, and he'll be harder to comfort and may not sleep as well. We know he seems to sleep better in the swing than in his crib. Why not let him sleep in the swing? I also suggested they let him sleep in the car seat. This will keep him in a much more upright posture (adults with heartburn often sleep with a lot of pillows or with the head of their bed propped up) and keeps him securely snug. I cautioned them not to put the car seat on a table, bed, or any other surface. If they put him to sleep in one, it needs to be on the floor. Even gentle movement of the baby can cause most car seats to move across a surface and fall to the floor.

And if this is reflux, why not treat it? I prescribed some first-line antacid medication. I don't like putting babies or anyone else on medication, but sometimes you have to keep your eyes on the prize, which is helping the baby feel comfortable enough to sleep through the night. My job is not to minimize medication. My job is to make the baby's life better.

I had an assignment for dad, too. I told him that life is tough all over, and he was going to have to pitch in. I wanted him to take the middle-of-the-night feeding if there was one. If not, he would have to take the first feeding of the morning. The baby might indeed get hungry in the wee hours with the new regimen of comforting the baby without nursing every hour. Mom has plenty of pumped milk and the baby will take a bottle. So dad is going to get the big feeding while mom is going to get what I hoped would be at least 4 hours of uninterrupted sleep.

Lastly, they needed to establish a rock-solid bedtime routine. Doctors who treat insomnia note that the overwhelming majority of their adult patients have poor sleep hygiene. That means that they have the TV on, that sometimes they go to bet at 10, sometimes at 2. Maybe they sometimes eat before bed, sometimes not. People of every age respond to the ritualization of sleep, and the establishment of sleep cues. I suggested that every night at their chosen baby bedtime, they have the exact same routine. It might start with turning off most of the lights, then giving the baby a bath. Then they put on a fresh diaper, mother sings him a song while nursing, then more lights go off, then he is put in the crib in the other room (or the swing/car seat as above). With his transition object.

They're coming back in a few weeks. I don't know what has been working or not. When I do, I will post Part 4.

October 15, 2009

The Human Pacifier, Part 2

- The baby is my patient.

- The baby is OK, healthy and developing normally.

- Establish the health status of the baby, give the parents a handout (called, perhaps ironically, 'anticipatory guidance') and make an appointment for the next well-baby visit.

- The baby would shake his head violently when placed on the crib. No, that's not normal. A very careful exam of the child's head showed a pink, flaky area on the back of the baby's head. Cradle cap? Ringworm? (The baby's awful young for ringworm.) In the course of the long visit, while talking to the parents, I was making faces at the baby and watching his response. Smiling. Laughing. Scratching. Sure enough, the baby was sometimes scratching his head, his thighs, his stomach—pretty much wherever he could reach. So I didn't just look in his ears and listen to his heart. I gently ran my hands over his skin, and the sandpaper-like patches were obvious to the touch, but invisible to the eye. I don't know if the little patch on his head was pink because of the head thrashing, but I knew the baby had eczema. Studies clearly show that babies who are itchy (and adults too, by the way) don't sleep well. They don't sleep as deeply and awaken more easily and more often.

- The baby didn't like to be horizontal. He didn't spit up much more than usual, but he was spitting up after nearly every feeding. He seemed to sleep better when propped up in the swing, even if the swing wasn't going. Though every baby is born with gastroesophageal reflux, some of them show remarkable and rapid improvement in their irritability, sleep patterns, and willingness to be placed on their backs following basic anti-reflux positioning and medications.

- In the Pavlovian world of conditioning, who got to play Pavlov's Dog—the baby or the mother? Here' my interpretation of what was happening in the bedroom, where mother slept in the bed attached to the co-sleeper where the baby slept, while dad slept in the other room. As in the analysis of any two-part system, let's look at each component.

- The baby. Have you ever slept in a place (maybe grandma's house, maybe sleeping over at a friend's house) where somebody woke up early to bake fresh muffins in the morning? OK, maybe it was bacon frying in the morning before you were up. I'll come back to this in a moment. First, my view on the baby's sleep. Here's what happens. We cycle through various stages of sleep. In stage 1 sleep, we're just barely asleep; in stage 4, we are not moving, breathing slow and deep. In Rapid Eye Movement [REM] sleep, we talk in our sleep, move around a lot, and dream. I suspect that in the baby's REM sleep stage, he's vocalizing just as he did with me in the office. It's not crying, just making vocal sounds. In this stage of sleep, he's also moving around. Whether he's dreaming of breasts is anybody's guess. But he makes some sound, that mother is pre-emptively reacting to. Even if this is just a stage of sleep from which he will descend without help into a deeper and quieter stage. But mother picks him up and...fresh muffins! Now, not only does he have an incentive to jump out of bed and check out whatever delicious goings-on are happening in the kitchen, he is rewarded for doing so by the positive feedback of mother's touch and nursing.

- The mother. Anyone who's ever used an alarm clock to get them up for school or work knows that the alarm clock makes itself superfluous. For a few days, maybe a few weeks, on the same schedule, the alarm clock wakes us up. Sometimes groggy, we force ourselves out of bed and off to work. Even if we go to sleep way too late the night before, we still wake up moments before the alarm goes off. What's happening is that our brains have been conditioned in ways that I don't think are fully understood. Somehow we are programmed to awaken at a certain time every day. For new parents, they—or sometimes just mom—get so sensitized to the sounds from the baby or baby monitor that they hear these sounds even in a crowd or over the sound of a TV. The baby is smelling fresh muffins when he's not awake, but in a shallow-enough sleep stage to pull himself to wakefulness. Mom has been conditioned to anticipate the alarm before it goes off, and never lets herself get to a deep enough sleep stage for effective rest. She is also conditioned to awaken at the first sounds that come from the baby, whether or not they are a request for her services.

- The pair. This coupled system could, in a previous life, have induced me to attempt to model and analyze it. Suffice it to say that the baby does what comes naturally, with a spiral of positive feedback. The mother does what comes naturally, from the love for her baby and the willingness to sacrifice. But it's a dysfunctional system, in which the unsustainability of prolonged sleep deprivation of the mother will not have good or even benign consequences for the baby. Aha! The baby is my patient.

- The baby. Have you ever slept in a place (maybe grandma's house, maybe sleeping over at a friend's house) where somebody woke up early to bake fresh muffins in the morning? OK, maybe it was bacon frying in the morning before you were up. I'll come back to this in a moment. First, my view on the baby's sleep. Here's what happens. We cycle through various stages of sleep. In stage 1 sleep, we're just barely asleep; in stage 4, we are not moving, breathing slow and deep. In Rapid Eye Movement [REM] sleep, we talk in our sleep, move around a lot, and dream. I suspect that in the baby's REM sleep stage, he's vocalizing just as he did with me in the office. It's not crying, just making vocal sounds. In this stage of sleep, he's also moving around. Whether he's dreaming of breasts is anybody's guess. But he makes some sound, that mother is pre-emptively reacting to. Even if this is just a stage of sleep from which he will descend without help into a deeper and quieter stage. But mother picks him up and...fresh muffins! Now, not only does he have an incentive to jump out of bed and check out whatever delicious goings-on are happening in the kitchen, he is rewarded for doing so by the positive feedback of mother's touch and nursing.

- The problem of mother's lack-of-sleep, and dad sleeping in the other room, is a problem for the baby and needs to be fixed, if possible.

- What difference would a diagnosis make? The baby was not in medical danger from some unidentified disease. I just needed to get this mom through the night.

Next post: What I did, what I told the parents to do.

The poster at top is in my office. It's from the Tony Nourmand collection originally, and is published in Exploitation Poster Art (Aurum Press 2005), page 170. It's from 1934 and was about parents whose behavior made them guilty. I like it for the irony of 75 years later: not parents being guilty, but parents feeling guilty.

October 11, 2009

The Human Pacifier, Part 1

- Baby won't sleep solid 2-6 hours at 5 months;

- Mother not getting a sustainable amount of sleep;

- Father sleeping in another room.

- The baby is insatiably hungry, but is growing normally;

- The baby hates being horizontal, but is OK in the swing or carseat;

- The baby shakes his head on the crib mattress;

- The baby nurses a lot during the day.

- The baby is growing and developing normally, so I can reassure the parents that they will all get through this difficult time and that they should return in 2 months for the next scheduled well-baby visit. (This, by the way, is the 'standard of care.')

- I should try to diagnose the reason for the baby's frequent awakenings, and treat this or at least help the parents understand this.

- I should avoid 'medicalizing' this normal variant of infant behavior and development. I shouldn't agree with the parents that the baby has a problem. It's their problem having difficulty living in their otherwise-normal baby's life. Why does every minor inconvenience need medical intervention? Does this require a diagnosis?

- Is the baby suffering? After all, he's my patient. If the baby—laughing and smiling with me in the office—is none the worse for wear, everything else is incidental to me as his physician.

- Do I try and fix this? In the early 19th century, a popular medicine for babies was Godfrey's Cordial, a liquid mixture of molasses, sassafras, and opium (sometimes brandy). The good news is that it worked great. The bad news.... If I decide to try and fix this, what exactly do I fix? What's broken? What, when all is said and done, is my job?

October 7, 2009

Mystery Cases, Mystery Medicine Part 1

Here’s how mystery cases typically present: Doctor, my kid has a fever. How’s he acting? Fine, playing as usual. But he has this fever.

If it were an adult patient, maybe it starts with: Doctor, I’ve been feeling a little tired recently. I just don’t have the energy I used to have.

Mystery cases don’t begin with a bizarre mixture of ankle pain, ringing in the ears, hair loss, and loss of feeling in the right thumb. And did I mention the canoe trip up the Ximim-Ximim River? The trip where you had to drink whatever water was at hand?

Mystery cases don’t begin with a bizarre mixture of ankle pain, ringing in the ears, hair loss, and loss of feeling in the right thumb. And did I mention the canoe trip up the Ximim-Ximim River? The trip where you had to drink whatever water was at hand?

So mystery cases don’t start as mysteries, they just become mysteries over time. Usually.

This time is very different, and I will try to chronicle the case as it unfolds.

I received a call from a man who told me that his son had a stomach ache, and he wanted to come to see me.

The boy of 11 had severe abdominal pain for 8 months. Including last Spring, he’s missed a total of about 2 months of school. He has had some blood tests (don’t know what yet) and had an endoscopy (unclear as to which end, but I’d guess that somebody looked at his stomach with a TV camera to make sure he didn’t have an ulcer. If they got to an endoscopy, I have to assume they did some other imaging too, but I don’t know what. The father said that he was told everything is normal. He was advised to wait and see. He was recommended to me, but I’m not sure exactly by whom. Looked me up online, and got the impression that I wasn’t a ‘wait and see’ kind of doctor.

I am, in fact, often a ‘wait and see’ kind of doctor. But not when this kid’s in pain. This was going to take time, and if there were something that smart and perhaps more expert doctors than myself didn’t see or connect, it was not going to be obvious. I was booked solid, so I told him to meet me in the parking lot on Sunday, and I would open the building and open my office for him so we could have at least a couple of uninterrupted hours.

Here’s a mystery case from the first contact. It has already unfolded as a mystery. I think that might be tougher, actually. I’ll have to look through every test that was done and guess what other doctors were trying to look for or rule out. So there will be a lot of homework.

In this case, a father found me on his own. Sometimes I get referrals from other local doctors with difficult cases.

I am bothered most by a child in pain. Perhaps, as doctors are notorious for undertreating pain (especially in children and the elderly), this is really all about pain control somehow. Maybe it’s just that his previous doctors didn’t spend the time to get the whole story, thus missing some essential clue. I’m worried that I just won’t deliver a helpful answer, meaning one that will help the child.

Mystery cases only become mysteries when what you’re doing isn’t working, when what the patient’s disease is doing doesn’t fit with your expectations.

Sometimes, my job is to make a diagnosis. With a known diagnosis, so the theory goes, a known treatment can be applied for a known expected result. I say theory because there are plenty of diagnoses for which there are no effective treatments, so getting to the diagnosis is at best an academic exercise and at worst is costly and unpleasant. A good example is the common cold. There really aren’t good treatments for this basically benign disease. There are expensive exotic antiviral medications that might work if given early in the course of the disease, providing the cold is due, for example, to adenovirus and not rhinovirus. To determine this, one would have to have a nice sinus rinse (I don’t recommend it) at the first sign of a sniffle. This proud sample would have to be whisked off to a lab which has the capability of Polymerase Chain Reaction DNA amplification and analysis, and is willing to put aside the Ebola they’re working on so you can save half a box of tissues.

So I really look upon my job as making people better. Sometimes it’s through a diagnosis. Sometimes it’s just making them feel better.

Mystery cases, then, are more than just cases without a clear diagnosis. Every kid with a runny nose could be….

Maybe I should call this Dr. Wolffe’s First Law: Never ask your doctor, ‘What could it be?’ Yet that is one way I can approach a mystery case. As the doctor mixes in each new piece of information, many possibilities get ruled out and a few remain. Eventually, the doctor must make a decision. What’s possible? What’s likely? What fits best? Which diagnosis is the most important? Here’s an example. A kid is coughing, so much that he’s having a hard time getting a breath. Maybe it’s not asthma, and a steroid medicine won’t help him. In fact, he may have some other symptoms that don’t fit with asthma. But if it is asthma, and he doesn’t get the steroid medicine, he could be in the Intensive Care Unit in a matter of hours. If he gets the steroids, he could go to school tomorrow. It’s conceivable that I could choose to treat a diagnosis that is not the most likely, but is the most dangerous if I don’t treat it.

Tomorrow is Sunday, and I’m seeing this child and his family for the first time. The only thing I know for sure is that it is a mystery case.

October 3, 2009

Cough #1: Breathing vs. Sleeping

Our government, which is to say taxpayers, offers insurance that commercial insurers would never come near. It’s flood insurance, for people who live on one of America’s great flood plains. According to the website, “30% of all flood insurance claims come from areas with minimal flood risk.” I’m

Our government, which is to say taxpayers, offers insurance that commercial insurers would never come near. It’s flood insurance, for people who live on one of America’s great flood plains. According to the website, “30% of all flood insurance claims come from areas with minimal flood risk.” I’m  good at math…so 70% of the claims come from areas with major flood risk. You know the 3 most important things in real estate: location, location, location. So we may not be able to predict the timing of a crisis, but we know for sure that one will come.

good at math…so 70% of the claims come from areas with major flood risk. You know the 3 most important things in real estate: location, location, location. So we may not be able to predict the timing of a crisis, but we know for sure that one will come.

A working mother called. She said that her son, 10, has been coughing for a week, and it’s been getting worse. He’s been missing school, and that’s just not working for her job or for his dad’s. Would I prescribe some cough medicine for him, since none of the stuff they bought at the pharmacy seems to be helping.

I’ve known this boy for about 10 of his 11 years. He’s had asthma for most of that time, and—to be blunt—his parents just have not pushed him to keep up with his daily medicine. Every time I see him it’s a crisis, and he often misses important follow up appointments.

Here’s what happens. He’s having a hard time breathing. Finally, his parents take him to the doctor, who prescribes the right medicine. He takes it, feels better. Nobody in the family sees any need to continue taking medicine when he’s not sick [please see The Medication Paradox] so he stops. They don’t show up for the follow up appointment in which I had planned to reduce but not eliminate his medication and to fine-tune what he gets to prevent subsequent crises. But this doesn’t happen, so the predictable crisis recurs.

I told her that I had to see him, and reluctantly, she brought him to the office.

The thin boy I saw before me was breathing a little fast, but not coughing much. I asked him if he minded missing school. He said, ‘Yes,’ and started coughing. A few minutes later, when I asked him to take a deep breath, that set him off again. He couldn’t speak more than a word or two without erupting in coughing. He was solidly in an asthma attack, and I told him and his mother this. I prescribed the appropriate regimen and told his mother as I handed her the prescription, ‘Get this filled right away and give him the full dose immediately. It won’t start helping for hours, and he needs to be better before tonight.’

I called that evening to follow up. I could hear him coughing in the background. I was told that he wasn’t better, but he was in good spirits and didn’t complain of difficulty breathing. I was in their living room in about 30 minutes. He looked about the same as when he was in the office, about 8 hours earlier. I couldn’t figure out why the steroids hadn’t helped—indeed this was an ominous sign that had hospital admission written all over it. I asked what time he took the medicine.

“Oh, he didn’t take it.” I admit to expressing more than passing curiosity about this, given my careful instructions to get it in him as soon as possible. “The pharmacist said not to give it tonight because it might keep him up. So we should give it to him tomorrow morning.”

Now, at this point in this completely true story, I hasten to interject that I adore pharmacists. My father was a pharmacist. Pharmacists have caught my errors and helped my patients.

This was not one of those times. Luckily for this child, I was standing there in his living room at 9:30 at night watching him take the medicine that might indeed keep him up all night, but breathing.

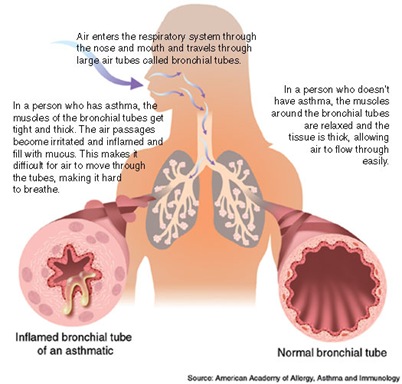

In asthma, the airways, those tubes carrying air into the deepest reaches of our lungs, get inflamed and irritated. When they are inflamed—just like other places in our bodies—they swell. But there’s a problem when the walls of a tube swell. The inside diameter of the tube gets smaller. It feels like breathing through a straw.

What we try to do medically is first, get the tubes to relax so they get a little bigger, making it easier to breathe. But as soon as this medicine wears off, the problem starts over since everything is still inflamed. So we also use anti-inflammatory medicine to reduce the swelling.

For the record, the medicines that we use with asthma can indeed have an insomniac effect. The steroids (not the kind that build muscle) can even cause some distressing behavior, especially in children. Albuterol and medicines like it (often dispensed in inhaler devices) can make your heart beat faster and make your hands shake. It might be true that these can cause a person to have trouble falling asleep. But people who are several days into an asthma exacerbation (the non-PC term used to be asthma attack) have not slept in days because they’re up all night coughing and trying to get a breath. When this primal hunger for breathing is relieved, no matter how stimulating the medication, they are often so relieved that they fall asleep restfully without a problem.

He was better within hours, and went to school the next day. We set up a follow-up appointment for Saturday. He missed it.